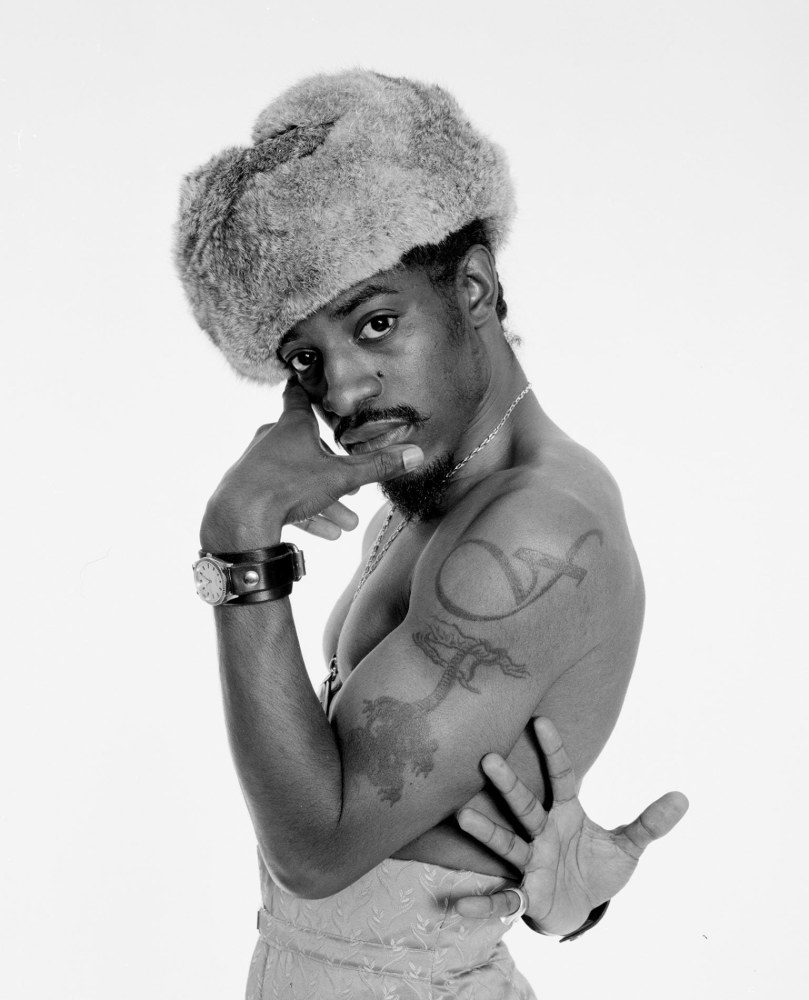

Every hip-hop fan knows the images: The Notorious B.I.G. rocking the "King of New York" crown, Tupac Shakur with the double-finger salute, Jay-Z peeking through his hands as he throws his diamond up. Now, journalist Vikki Tobak wants to share the stories behind these images as recalled through the words – and the lenses – of the photographers who shot them. The result is “Contact High: A Visual History of Hip-Hop.” In hip-hop fashion, the book's title is a play on words. Before digital photography, a contact sheet was the photographer's working diary, displaying all the images from a roll of film in one place so the shooter could select the best images.

As Questlove, beatkeeper for the The Roots, explains in the book's foreword, imagery has long been integral to music. The Roots studied Run DMC and Marvin Gaye covers in composing their own albums' artwork. Contact sheets, he writes, go further, telling the stories – of the photographer, the artist, the setting and the era – that a single image alone cannot convey. "The facts behind how those photos came to be are so much more complicated," the drummer writes. "Those shots are selected from a stream of Things Seen – in other words, part of a collection of many photos that exist of the moment one second before it, or one second after, or ten degrees to the right, or ten degrees to the left." “Contact High” bills itself as an "intimate look at the making of the imagery that shaped the sound."

From hip-hop's ascent through Kool Herc and the Cold Crush Brothers, to the baton being passed to N.W.A., the Beastie Boys and Nas, to the birth of Slim Shady and the demises of Biggie and Pac, to the superhero origin stories of Nicki Minaj and Kendrick Lamar, before they started stacking platinum plaques, the photographers paint a vivid timeline of a most American phenomenon. "Some of these photographers hadn't looked at these photographs or their contact sheets in years. Their rolls of film – many stored away in shoeboxes and closets – held iconic moments that were tucked away, still unprocessed,” Tobak writes in the book. The lensmen and women speak to moments both poignant and puerile. The stories – as Erykah Badu, who is featured twice in the book, says – go “on and on and on and on, all night, till the break of dawn.” There’s Eazy-E showing up to a 1989 Venice Beach photo shoot wearing a bulletproof vest, “I think … for legitimate reasons,” recalls Ithaka Darin Pappas.

Glen Friedman is reminded how the Beastie Boys selected a grainy faxed image – rather than the high-res image itself – for the cover of “Check Your Head.” He writes, “It was typical Beastie Boys shit. You just gotta laugh.” Wu-Tang Clan had to be convinced to don ski masks for the “Enter the 36 Chambers” cover shoot at an abandoned synagogue on the Lower East Side, Danny Hastings writes. U-God, Method Man and Masta Killa never showed up, he says. Eric Johnson remembers going to New Orleans in 1999 to photograph Juvenile and The Hot Boyz and capturing a teenager by the name of Lil Wayne, pre-face tattoos, trying on a pair of Reebok classics in a department store. Hoping to capitalize on an up-and-coming Chicago rapper, Nabil Elderkin bought kanyewest.com in 2003, only to trade it for a photo shoot when Ye’s label offered to buy it.

At a diner in Queens, circa 2008, Angela Boatwright told Nicki Minaj “to lay on the countertop, hold pancakes, play with syrup — the usual kind of thing. She was down, anytime I asked her to do something lascivious, she was down,” the photog recalls. Biggie is featured in many anecdotes. In one, he obsessed over a Brooklyn dock selected for a photo shoot, repeatedly saying, “This is where they dump the dead bodies.” In another story, Michael Lavine photographed Biggie in a Queens cemetery for the “Ready to Die” cover, neither man realizing Biggie would be slain a few weeks later. Tobak, the author, said her favorite part of the book also involves the Brooklyn rhymesmith.

Barron Claiborne wasn’t exactly known for shooting rappers when Biggie showed up at his studio near Wall Street for a Rap Pages magazine shoot. He felt images of rappers had been cliché, and Claiborne “wasn’t interested in stereotypical negative imagery of black people,” he writes. To him, the rapper was “a big West African king,” and he wanted him portrayed as regal in the photos. The idea was almost derailed by Puff Daddy, who owned Bad Boy Entertainment, Biggie’s label. Puff thought the crown made Biggie look like Burger King, but Biggie convinced Puff it was “a cool concept,” Claiborne writes. "This photo is about hip-hop, but it's also beyond that. This was simply about photographing Biggie as the King of New York. He is depicted as an almost saint-like figure. This shot is the shot and it's iconic. I still have the crown, too,” Claiborne says, adding he was honored to hear that mourners carried the image during the rapper’s funeral procession days later.

It’s a fascinating narrative, but it’s not the reason Claiborne’s encounter with Biggie is Tobak’s favorite. Rather, it’s an image on the contact sheet showing a crowned Biggie, head cocked to his left, bearing a grin so bright it’s blinding. “That one shot of Biggie smiling on the contact sheet – for people who knew Biggie, whenever they see that, ‘that’s the Biggie I know’ … not the stern one on the album and Rap Pages cover,” she told CNN. Tobak was first drawn to music as a youngster. After growing up in what is now Almaty, Kazakhstan, a 5-year-old Tobak arrived in Detroit in the late 1970s after her Jewish father applied for refugee status and fled what was then an autonomous republic within the Soviet Union.

Music – first, the croonings of Aretha Franklin and Stevie Wonder, and then The Electrifying Mojo, a local DJ who helped introduce Prince to Detroit and promoted the Motor City’s burgeoning techno scene – was integral to understanding America, its language and its history, Tobak said. She grew up in a diverse community, but found that in Cold War America people had preconceived ideas about Russians, even those who had fled the Soviet Union. “A lot of the white kids in the school were like, ‘You’re a spy. You’re weird,’” she said. Her black classmates and neighbors, on the other hand, empathized and welcomed her. “It was beautiful. They made me feel comfortable with the culture and also drew me into it,” Tobak said.

Tobak’s arrival in the States, of course, coincided with the rise of a nascent genre of music called hip-hop. By the mid-1980s, Public Enemy and EPMD were making names for themselves with songs about reclaiming power and demanding respect. “That appealed to me,” Tobak said. “I loved it so much I wanted to move to New York City at 18 and be a part of it.” Which she did, first as a cashier/doorwoman/receptionist at Nell’s, the Manhattan nightclub where Biggie’s “Big Poppa” video was shot. Russell Simmons and Tupac were regulars, and it was no big deal to catch DJ Clark Kent or Stretch Armstrong working the turntables on a given night. Tobak took a job as a public relations director for Payday Records, which at the time had five employees. There, she met hip-hop trailblazers Guru and DJ Premier, better known as Gang Starr, who have two album shoots featured in the book. Jeru the Damaja and Mos Def (aka Yasiin Bey) were also on the Payday roster.

Tobak accompanied the musicians on photo shoots, where she met many of the photographers included in her book. Later, she worked as a journalist for Vibe, Paper and Mass Appeal, among others, expanding the network she’d later tap to curate “Contact High.” Her connections proved helpful more that once, notably when Glen Friedman – who’d shot the “Check Your Head” image and a Public Enemy album cover – declined to break his rule about never showing his contact sheets. Friedman has his own photo books and “is meticulous about telling his story in the right way,” a stance Tobak respected, she said. Fortunately, they had a common friend – Gary Harris, the famed A&R man credited with discovering D’Angelo – who convinced Friedman to share his contact sheets, which accompany two of the best backstories in the book. (Harris passed away earlier this year, before the book was published.)

With “Contact High,” Tobak hopes to illustrate the evolution of hip-hop. The photos within her book’s pages serve not to promote an artist, but rather to “tease out these deeper layers, the spaces where hip-hop was born and took place and took shape,” she said. Ancillary characters, as well as neighborhoods – whether it’s Nas in Queensbridge, A$AP Rocky in Harlem or Kendrick Lamar at Tam’s Burgers in Compton – are as important as the artists themselves, she said. “The neighborhood is everything. They didn’t want to impress the mainstream,” she said. “More than anyone, they wanted to impress their small crew, their block.” She also wants to highlight the photographers, who, like their muses in many cases, were young, black and unknown when they captured the historic images. “I want the reader to come away appreciating that hip-hop was born from a community (where) there were all these amazing image makers that pointed their cameras at a moment that wasn’t mainstream,” she said. “They just thought it was important.”